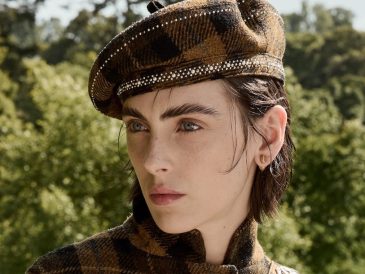

Lead ImageThe Filial Daughter孝女Photography by by Mengyu Zhou

“I don’t know if you can call it a healing process, but it felt like coming back to the place I was always running away from,” says Berlin- and Paris-based photographer Mengyu Zhou of her project The Filial Daughter孝女, which is currently on show as part of a group exhibition at Konnekt Berlin. “I’m finally able to tell its story.”

In Zhou’s series, which stars her cousin Orange, she offers an intimate glimpse into the life of a woman bound by societal and familial expectations, which remain rigid and stifling amid a rapidly changing China. The images of Orange in her hometown Wenzhou, an industrial city in China’s Zhejiang province, are sleepy and atmospheric. She’s pictured as she dresses herself, loiters in a parked car, or listlessly sits on a hammock in the baking sun. But beneath that layer of ennui is an ongoing narrative of selfhood against all odds.

Now 29 years old, Orange grew up with Zhou in Wenzhou, but the two were separated when Zhou moved to Germany with her parents at the age of six. Orange, intent on living elsewhere like her cousin, dropped out of high school to apply abroad, only to have her parents cancel her application without consulting her, Zhou recalls.

Sans diploma, Orange filled her days with odd jobs and was labelled a poor marriage prospect, her only redeeming quality being her youth. She was then told to marry or be set up with someone; she married a boyfriend she’d met in her early twenties but their relationship ended within a year. Then, she went from facing pressure to marry to grappling with the shame of being a female divorcée. To this day, her family still insists on her remarrying.

On naming the series, Zhou says: “孝女 came straight into my mind but I struggled to find an English or German word as there’s almost no direct translation.” She recalled speaking to non-Asian visitors who had trouble understanding the dynamics around duty and filial piety. “This is what we grew up with. Being a daughter, you’re born with this expectation to take care of your family, to be the thoughtful person, to always be kind and understanding. People in the West will say, why can’t [Orange] just move away, and cut ties? It’s not that easy, because to this day she’s trying to prove that she’s a good daughter.”

For Zhou, Orange’s story is not only close to home, but a reminder of what her life could have been in an alternate universe if she stayed in Wenzhou. “I wanted to run away from it and save every woman from [the] place, but it’s a love-hate relationship. I love it so dearly; it raised my parents and all the people I love,” she says. “My life isn’t perfect, but I have the freedom I have, which I’m deeply grateful for.”

Archive photos and urban landscapes also populate the series. Zhou’s reframing of sepia-hued family portraits and Wenzhou’s city vistas – real-life collages of high-rise developments and inky mountains – shed light on the discord between old values and growth in all its digital and concrete forms.

A feeling of being left behind by progress now pervades Chinese youth culture (躺平 (tang ping) meaning lying flat, or 擺爛 (bai lan), letting it rot, being the more viral examples). But Zhou’s work is stronger for its focus on women, who are not only struggling for meaning and mobility but seeking independence and selfhood in a culture that hasn’t left its patriarchal traditions in the past. That thread will continue through her future projects, which she hopes will take the form of conversations with other women in Wenzhou. “As long as I live, there will be an ongoing conversation between me and my hometown. I’ve come a long way – now I can be there for two months without going crazy,” Zhou laughs.

The Filial Daughter孝女 by Mengyu Zhou is on show as part of a group exhibition at Konnekt Berlin until June 23.