Art galleries have been places for the gathering and exchanges of ideas for centuries – think of the 19th century Parisian salons, where art caused scandals and flocking crowds; which, incidentally, was echoed in London in the 1990s and the tabloid-mongering YBAs. It was shortly after these that the Tate Modern was founded, cleaving the London art scene neatly into the classical (Tate Britain) and the cutting-edge. And rather than the pillared halls of Tate Britain it was the concrete Tanks of Tate Modern where Gucci chose to show its latest Cruise collection – creative director Sabato de Sarno’s first.

That’s in part because De Sarno remembered walking those halls as a fashion student. “I owe a lot to this city, it has welcomed and listened to me,” he said. But, it’s also tied to the house itself, “whose founder was inspired by his experience there.” Guccio Gucci worked as a bellboy at the Savoy hotel as a young man – witnessing the to and fro of the moneyed classes, and toting their expensive luggage, gave him his big business idea. So, in a sense, although Gucci was founded in Florence, it was born in London. So this collection was a homecoming for the creativity of the brand, and of De Sarno himself.

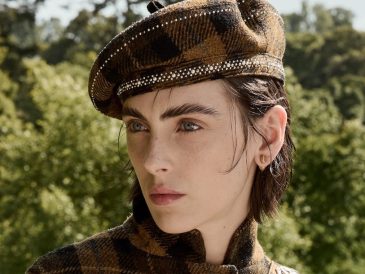

Certainly, there was a freshness to the collection, a youthfulness and a sense of growth, flowering. The concrete tanks of the Tate were planted with a cornucopia of foliage, crunched underfoot by Gucci ballet flats. The shoes throughout were hardy, practical – feet on the ground, rather than a flight of fantasy. And the same was true of the clothes which, rather than an idyllic idealised idea of British dress – Beefeaters, princess dresses and the like – were rooted in reality. Sure, not every Brit wears a pussy-cat bow blouse, but there was a sense that they could, and maybe they would. There were a few overt nods to Britain, especially in checked, Mod-neat tailoring and embroideries that seemed to reinterpret tartan as trembling fringe embroideries. And, of course, the equestrian stuff – which is a Gucci-ism, but one that came from Guccio Gucci’s experience in London at the turn of the 19th century. But overall, this was a collection that could and would travel – no Brexit chauvinism, or indeed touristic simplification of Englishness. It bore out something De Sarno said before the show: “I like taking something that we think we know and breaking away from its rules.”

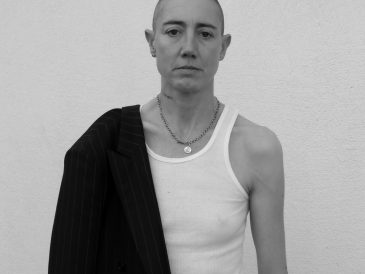

Britain is full of rules, of course – manners, class boundaries, not least dress codes and uniforms from Royal Ascot attire to military regalia, right back to the blazers and house ties of school days. So De Sarno had plenty to play with, and mixed different rules and strata of dress together to form a fusion that felt new. Bomber jackets were slung over evening dresses, tailoring clashed with transparent slips, embroideries transformed neat little coats. His flowering idea was literally represented with floral embroideries – not of precious blooms but of the humble daisy, worked into elaborate embellishments on fresh organza or into all-over riots carpeting tailoring. The message seemed to be a clash between the natural and romantic, and the strict and modern – wildness, barely contained.

But it wasn’t the Clash that had the last say, rather Blondie – that was the name of the archival Gucci bags De Sarno revived and blew up for the show. Apparently, they’re not connected to the band – although Debbie Harry sat front row, and one of their greatest hits, Heart of Glass, soundtracked the finale. But it was melded with Philip Glass, rock with rigour. Another rule broken.