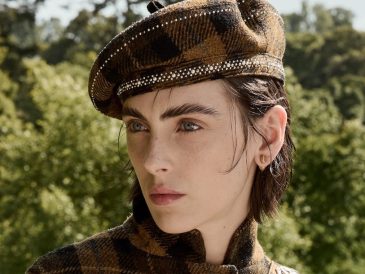

Lead ImageBertie BrandesCourtesy of Bertie Brandes

Bertie Brandes has been self-publishing for years – most prominently with Mushpit, a print magazine she produced between 2010 and 2018. Emerging out of a dissatisfaction with the ads-dominated, often anodyne glossies that dominated the newsstands back then, the publication took an experimental and satirical approach to magazine-making, tackling subjects from boys and flatmates to heavier topics such as grief, heartbreak and modern malaise. And while she contributed to other publications (including Dazed, i-D, Vice (RIP), and more) too, it’s always in her personal work that her creativity has been most unbounded.

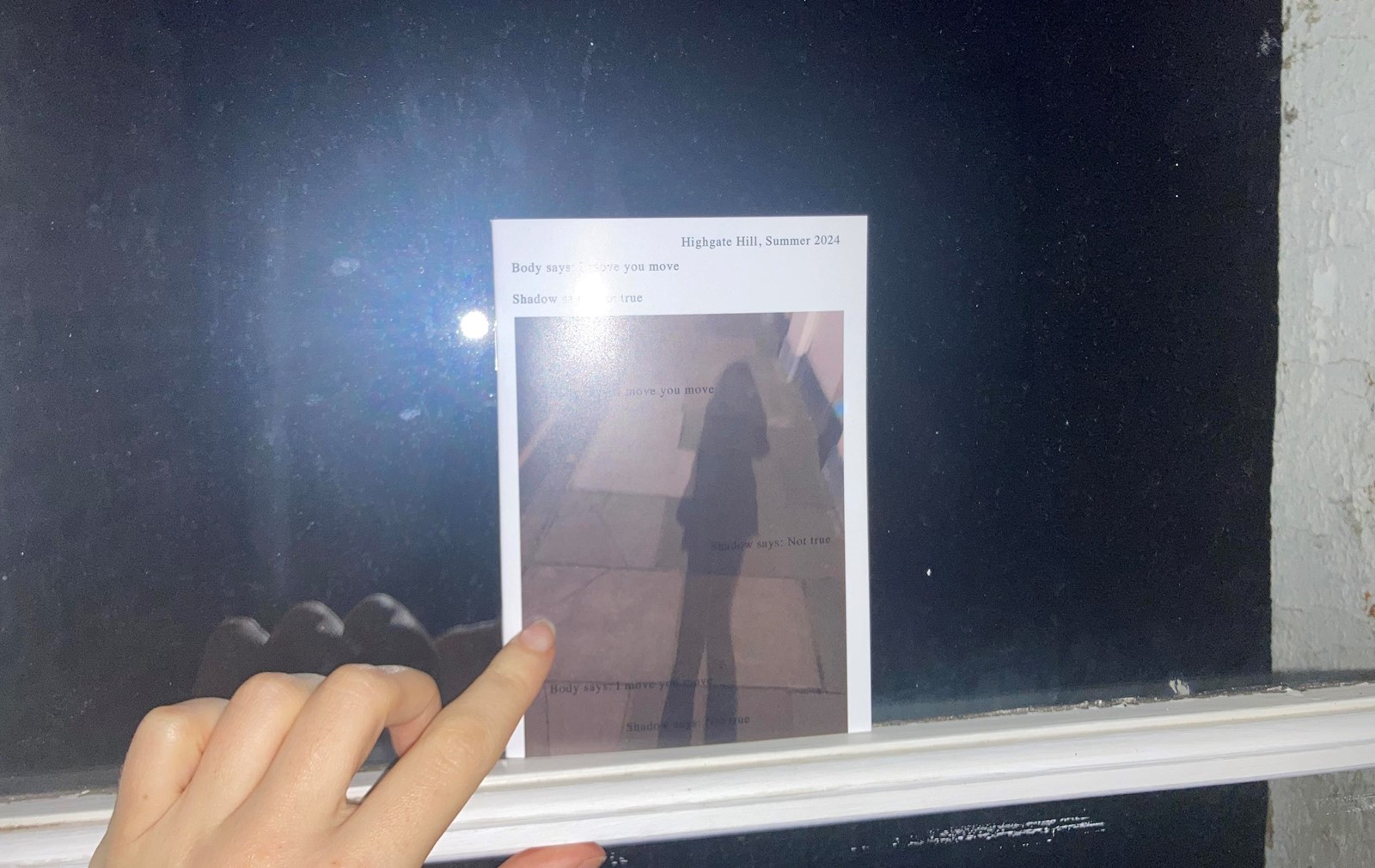

These days, Brandes works in advertising as a creative and copywriter, but she continues to make her own publications. Working predominantly in the zine format, she’s currently in the midst of a series exploring, as she puts it, “the universal experiences of alienation”. The latest chapter is published this month; titled Body Moves, Shadow Moves and accompanied by self-shot iPhone photos, the publication attempts to remap a chaotic past relationship on a walk through Highgate, where two characters – the “Body” represents her partner at the time, and the “Shadow” represents her current self – engage in a conversation with each other.

Here, Bertie Brandes delves into this specific publication and into zines more broadly.

Ted Stansfield: As a self-described “zine girl” (got this from Twitter lol), I wondered if you could tell me what appeals to you about the format?

Bertie Brandes: God, I just love zines. I love the formlessness of them, I love the disdain that everyone treats them with. They feel completely pretentious and totally amateur at exactly the same time. I think they’re the perfect container for uncomfortable, unfinished feelings, and a great place to work things out. Zine girls forever.

TS: How has your relationship with printed matter changed over the years?

BB: I think I have zero tolerance for compromise now, although I’m not sure I ever did. For me, self-publishing is an act of total artistic freedom, no settling, no striking a balance. The radically personal poetry and photography in this zine feels a bit like the last frontier between me as a female writer and the institutions and industries that want to formalise and optimise expression.

TS: You say this is the next chapter in a body of work about alienation. How did you arrive at this subject?

BB: Pretty much everything I write is on some level just trying to process the constant insanity of being alive. Sometimes life happens as a series of hallucinations, other times you can be so physically trapped in your body, it feels like claustrophobia. My work kind of reverberates between these two modes, which I tend to wrap up with a pretty ribbon under the catch-all term alienation.

TS: Can you introduce this new chapter?

BB: This is the shortest and probably most conventionally ‘poetic’ of three recent zines I’ve published in the same print format. The first one took the form of a medical diary, the second was a sort of protracted mathematical equation about wanting, and this is a mediation on obedience and control. They all contain iPhone photos and an intermingling of distinct voices, some ‘universal’, others deeply personal, which gradually start to interact with one another. The slipperiness of boundaries between voices is very sexy to me.

TS: What is the third zine about?

BB: In the simplest terms it attempts to remap an extremely chaotic relationship from well over a decade ago, as I consider what drew me to its dynamic and why I still feel drawn to it in some ways. The relationship is mirrored in the complicated relationship all objects have with their shadows, at once identical and unsettlingly strange.

TS: The shadow is literal but also metaphorical. Can you explain the metaphor?

BB: Initially the “Body” represented my partner at the time, and the “Shadow” was me, which was a pretty straightforward metaphor of control and obedience. But on the walk that the zine documents, I was really struck by the movement of my shadow, how it stretched and warped and was more often flung on the road ahead of me, seeming to lead my body. I was fascinated by how that might redetermine the terms of the relationship I was exploring; that some integral part of me could have sought out the dynamic that played out between us, even that long ago. In some ways, the shadow came to represent the secrets we keep from ourselves.

TS: What is your own experience of alienation? And do you think modern/city life is particularly alienating or do you think that loneliness is just part of the human condition?

BB: I think our microcosm of corporate culture is getting pretty good at acknowledging the existence of ‘mental health’, whatever that means. But (in my experience) that acknowledgement has absolutely no bearing on what it is actually like to suffer mentally. I hope that I make work that speaks to and with people who sometimes wake up utterly bereft and have to try to figure out how to live, almost from the beginning, over and over again.

“I hope that I make work that speaks to and with people who sometimes wake up utterly bereft and have to try to figure out how to live, almost from the beginning, over and over again” – Bertie Brandes

TS: Are there any writers that have had an influence on you in terms of your writing in this context?

BB: So many! Moyra Davey, Anne Boyer, Jacqueline Rose and Sylvia Plath all come to mind as writers who drive me to keep trying to make things. In terms of the work itself, I am eternally inspired by random lines of text that I brush up against by chance, YouTube video titles from girls with binge-eating disorders, rambling descriptions of perfumes, people talking quietly on the bus. Unintentional moments of poetry that raise your heart rate – that’s really what I live for.

TS: What are you reading at the moment?

BB: I’m a complete moron who reads multiple books at once. At the moment it’s Maggie Nelson’s Like Love, a collection of poems by Anne Sexton, Deliver Me by Elle Nash, and funnily enough The Communist Manifesto, which me and my dad are tackling together in our shared Kindle library. There’s a kind of deliciousness to finding our way to Marx via Bezos.

TS: Finally, what do you hope people take away from this zine?

BB: I hope people find a bit of themselves in it – a moment of connection, maybe some discomfort. Or just be reminded that Highgate is a really nice place to walk around after dark.

You can buy the zine

Body Moves, Shadow Moves by Bertie Brandes is available to buy here and at Waste Store in London.